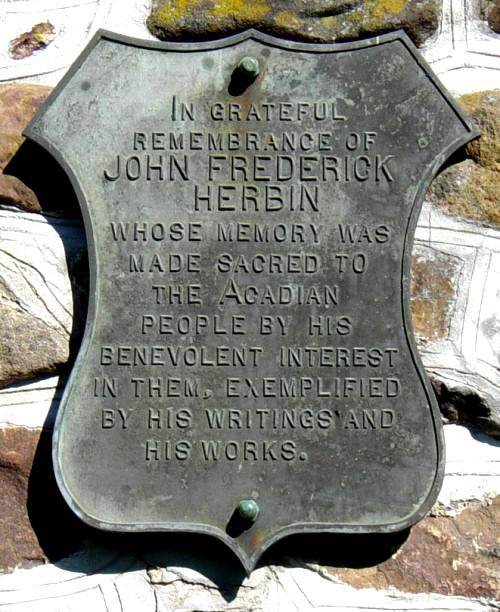

Photographs of monument

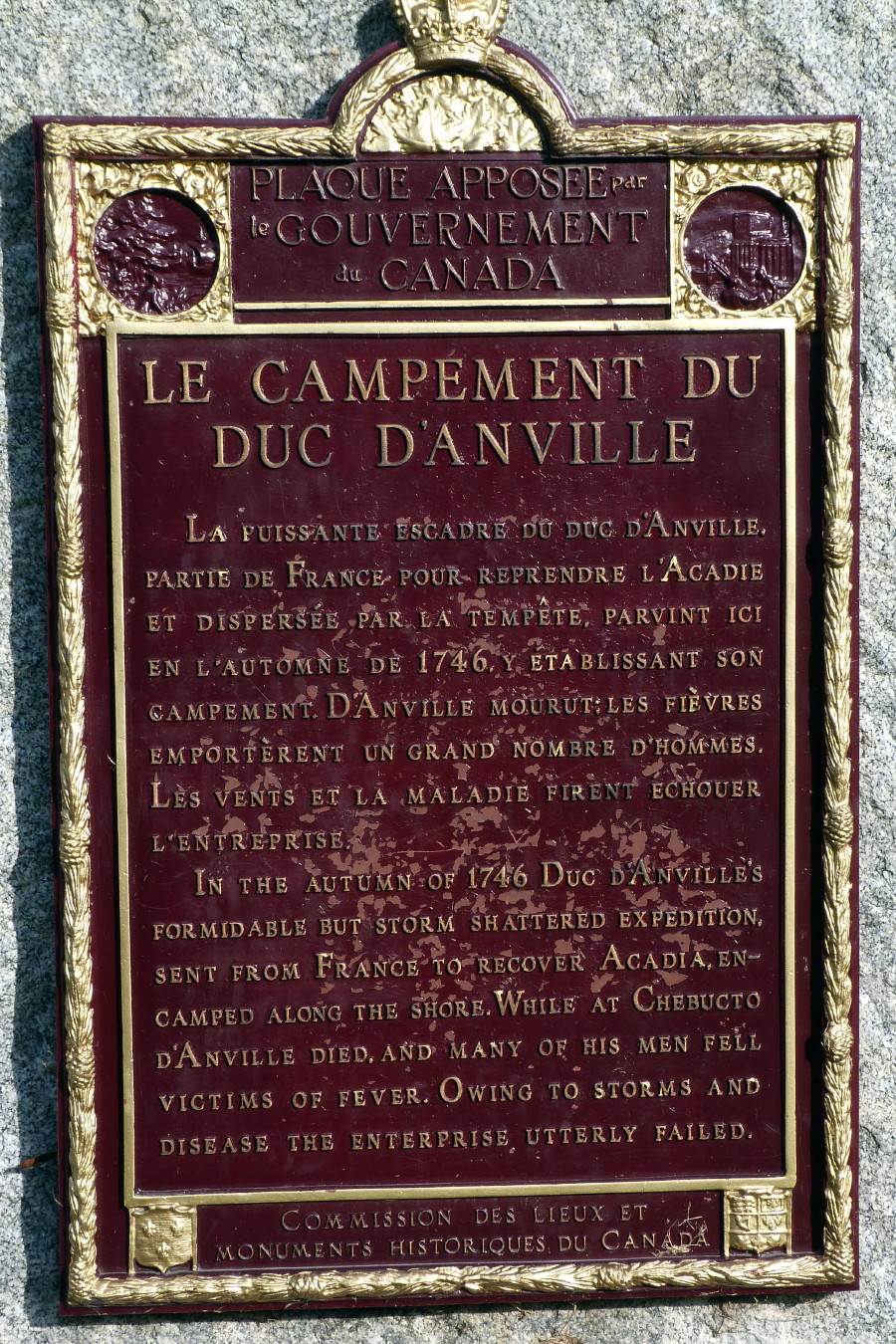

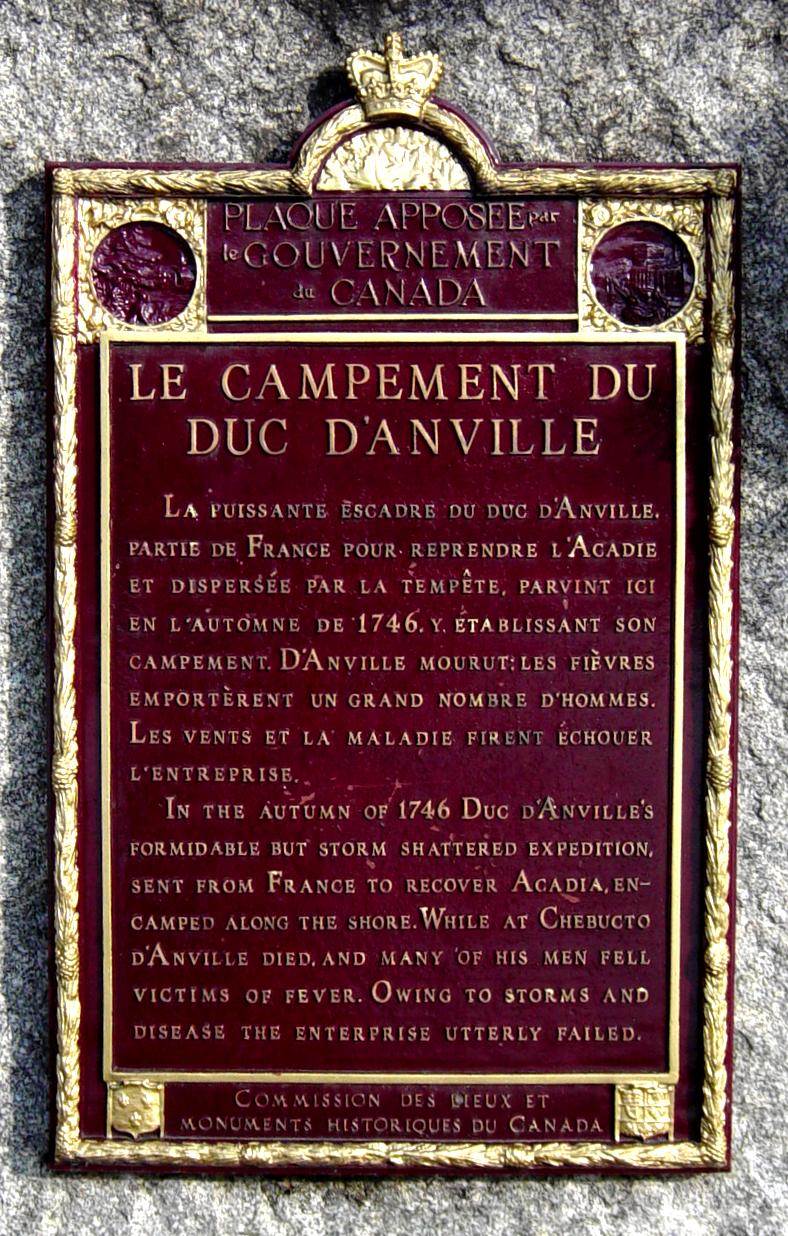

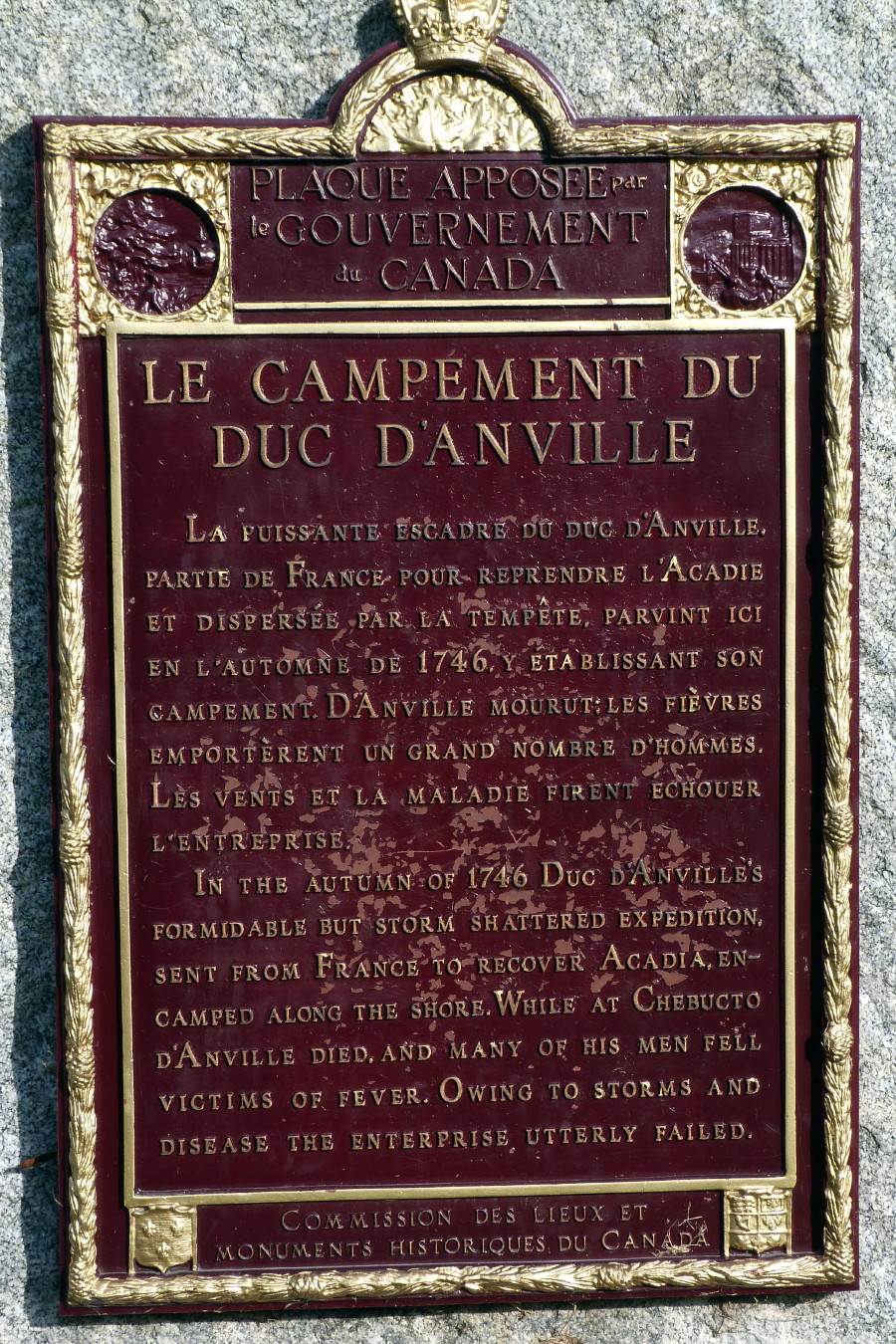

Duc d’Anville’s Encampment Chebucto 1746

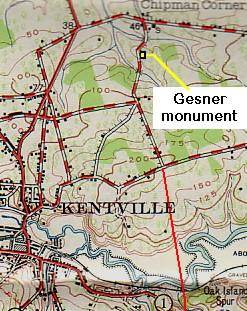

Rockingham Halifax Regional Municipality Nova Scotia

Located in Centennial Park, about 30m southeast from#199BedfordHighway

GPS location: 44°40’29″N 63°38’48″W

Google map showing this location

Photographed on 8 January 2008

Photographed on 8 January 2008

Photographed on 8 January 2008

Foreground: Bedford Highway

Photographed on 8 January 2008

Photographed on 21 November 2012

Photographed on 21 November 2012

…The fall of Louisbourg in 1745 and the removal of the inhabitants alarmed the French government, who now entertained fears for the safety of Canada and determined to take steps for the recapture of the lost stronghold, and with it the whole of Acadia, in the following year. Accordingly, a formidable fleet, under the command of the Duc d’Anville, sailed from LaRochelle, France, in June1746; while the governor of Quebec sent a strong detachment of fighting Canadians under Abbe Le Loutre; and emissaries were sent out among the Acadians as far as Minas to persuade them to take up arms on the side of the French.

In the autumn of 1746, Arthur Noble of Massachusetts, arrived at their destination. Most of the vessels carrying the others were wrecked by storms; one was driven back by a French warship. In December, however, Noble’s New Englanders, with a few soldiers from the Annapolis garrison, set out to rid Acadia of the Canadians; and after much hardship and toil finally reached the village of Grand Pre in the district of Minas. Here the soldiers were quartered in the houses of the Acadians for the winter, for Noble had decided to postpone the movement against Ramesay’s position on the isthmus until spring. It would be impossible, he thought, to make the march through the snow.

But the warlike Canadians whom Ramesay had posted in the neck of land between Chignecto Bay and Baie Verte did not think so. No sooner had they learned of Noble’s position at Grand Pre than they resolved to surprise him by a forced march and an attack by night. Friendly Acadians warned the British of the intended surprise; but the over-confident Noble scouted (scoffedat) the idea. The snow in many places was “twelve to sixteen feet deep,” and no party, even of Canadians, thought Noble, could possibly make a hundred miles of forest in such a winter. So it came to pass that one midnight, early in February, Noble’s men in Grand Pre fight in which sixty English were killed, among them Colonel Noble, and seventy more wounded, Captain Benjamin Goldthwaite, who had assumed the command, surrendered. The enemies then, to all appearances, became the best of friends. The victorious Canadians sat down to eat and drink with the defeated New Englanders, who made, says Beaujeu, one of the Canadian officers, “many compliments on our polite manners and our skill in making war.” The English prisoners were allowed to return to Annapolis with the honours of war, while their sick and wounded were cared for by the victors. This generosity Mascarene afterwards gratefully acknowledged.

When the Canadians returned to Chignecto with the report of their victory over the British, Ramesay issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of Grand Pre setting forth that “by virtue of conquest they now owed allegiance to the King of France,” and warning them “to hold no communication with the inhabitants of Port Royal.” This proclamation, however, had little effect. With few exceptions the Acadians maintained their former attitude and refused to bear arms, even on behalf of France and in the presence of French troops….

— Source: FullBooks.com

The Acadian Exiles, part 1 by Arthur G. Doughty, Toronto, 1916

Chronicles of Canada, in thirty-two volumes

Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton

Arthur G. Doughty Wikipedia

Sir Arthur G. Doughty Library and Archives Canada

The Acadian Exiles, by Arthur G. Doughty Project Gutenberg

Reference:—

Anatomy of a Naval Disaster: The 1746 French Expedition to North America

(book) by James Pritchard, McGill-Queen’s Press, Montreal, 1995

ISBN 0773513256

…The actual preparations of the fleet were fraught with delays, bureaucratic red tape and incompetence, and shortages of everything from money to edible food and drinkable water. Poor d’Enville endeavoured to establish order, but was too aware of his own shortcomings and inexperience to command respect. Pritchard analyses the preparations, the supplies, and the state of the ships themselves to provide a chilling picture of a second-rate navy and administration. Admittedly, the French were steering for a deserted shore, with no chance of help upon arrival such as English ships might expect, and they had to carry all their supplies for the outward and return voyages. The conclusion is that “The administration of the French navy displayed all the characteristics of an increasingly archaic mode of government unable to respond to current challenges or to assert its authority”. Poor weather added to these woes and delayed the expedition’s departure for weeks. Crossing the Atlantic to Nova Scotia proved harrowing, as the winds died and ships wallowed for weeks with little progress. Fresh food and water was already a problem when at last the fleet made landfall, and at that point disaster struck in the form of a vicious storm which scattered the ships, even forcing some to return to France. By the time the survivors actually found Halifax (the few Acadian pilots having died by this point) d’Enville was left with a battered, shattered, demoralized, and sickly force, with winter weather approaching. This section is harrowing reading, and at times one feels it is more appropriate as a description of early exploration voyages with their attendant hardships than as a recounting of a supposedly “modern” eighteenth century endeavour… The enterprise was a complete failure, not even attempting to reach a single objective, never sighting a British warship, never firing a shot in anger. Losses were immense: thousands of men, three capital ships, and several smaller vessels. A forgotten catastrophe was the death of up to half the Micmac Indians of Nova Scotia, who succumbed that winter to disease spread by blankets used by the sick French handed out to them for the winter. This book provides a very thorough account of the 1746 expedition, based on extensive archival and secondary research. There are insights in plenty on the condition of the French navy, but the discerning reader will also find much telling analysis of French absolutist government practices and administrative attitudes. That it deals with an almost forgotten failure in no way diminishes its value to historians of the ancien regime.

— Review by Paul Webb of Anatomy of a Naval Disaster: The 1746 French Expedition to North America by J. Pritchard

Canadian Journal of History, April 1997

Source:

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3686/is_199704/ai_n8759619

Link to Relevant Website

Duc d’Anville Dictionary of Canadian Biography

https://ns1763.ca/bio/7bio-91464-d’anville.html