Photographs of

Commercial Cable Company Telegraph Office

Brick building

Hazel Hill Guysborough County Nova Scotia

Located on the north side of Highway 16 at the Tickle Road intersection

GPS location: 45°19’38″N 61°01’44″W

West end of the building

Photographed on 18 September 2003

West end of the building

Photographed on 18 September 2003

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, south and east sides, shortly after sunrise

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The back (south side) of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The east chimney, Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The east end of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The main entrance of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, door installed in the 1980s

Photographed on 30 July 2005

Middle chimney

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The front (north side) of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, late afternoon

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The front of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The front of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

The northwest corner of the Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 30 July 2005

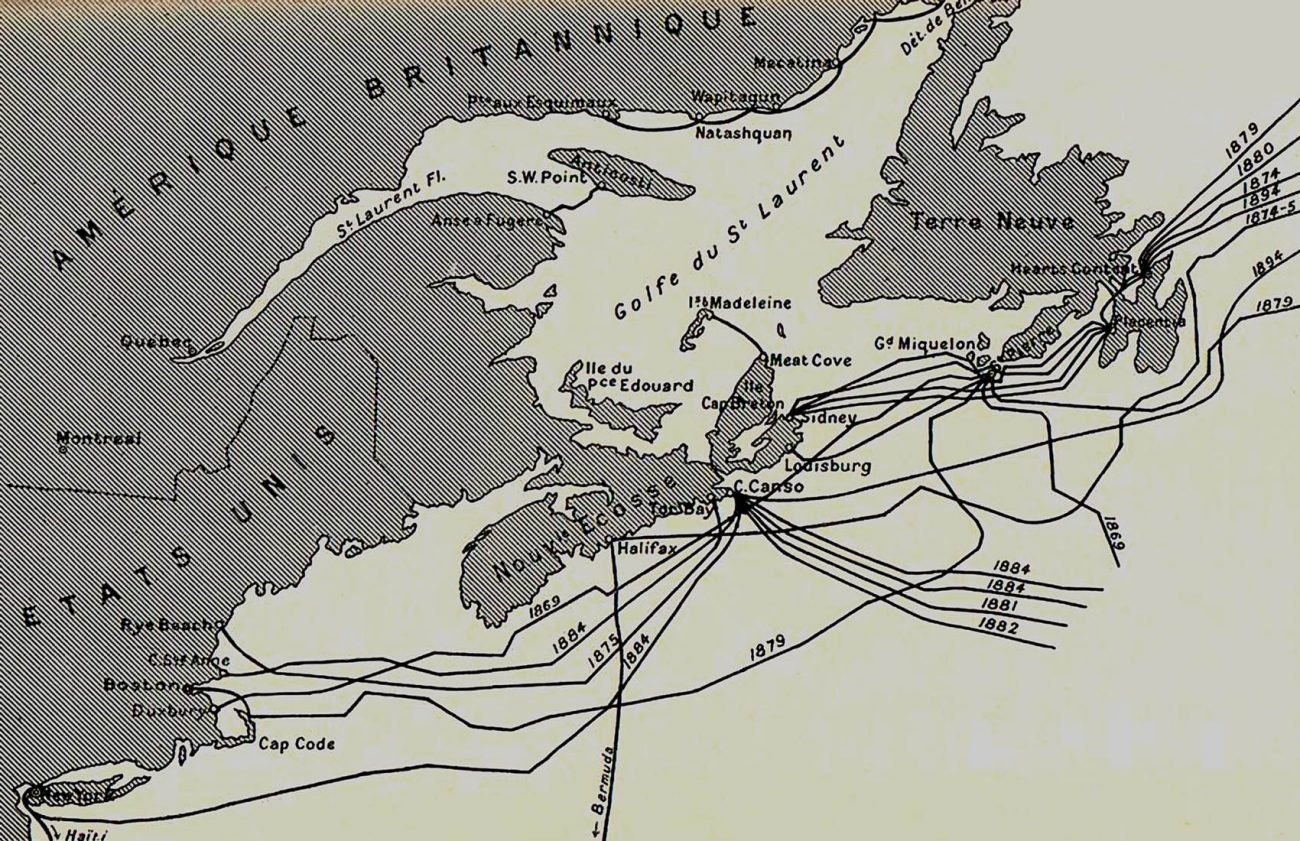

Commercial Cable Rehabilitation Society meets with MLA, MP

Clipping from the Guysborough Journal, 17 August 2005, front page

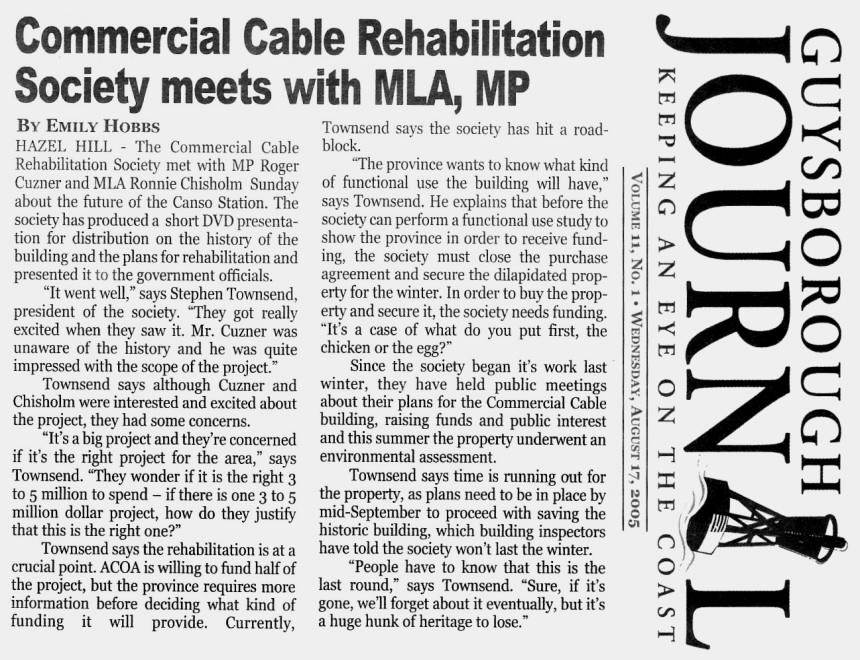

Funding comes through for Commercial Cable building

Clipping from the Guysborough Journal, 28 September 2005, front page

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, west and south sides

Photographed on 8 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, south side

Photographed on 8 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, south side

Photographed on 8 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

This view clearly shows the division between

the original 1888 building and the later extension

Photographed on 8 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, north and west sides

Photographed on 29 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building

Photographed on 29 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, east chimney

Photographed on 29 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, middle chimney

Photographed on 29 November 2005

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph building, southwest corner

Photographed on 29 November 2005

The derelict Cammercial Cable Telegraph Office as seen

from the Commercial Cable Trans Atlantic municipal park.

Photographed on 30 July 2005

Commercial Cable Trans Atlantic municipal park

Commercial Cable Company

J.W. Mackay and J.G. Bennett

The Commercial Cable Company was incorporated in New York in 1883 by two wealthy men, J.W.Mackay and J.G.Bennett.

James Gordon Bennett (1841-1918) (the younger) was the owner of the New York Herald newspaper, having inherited it from his father James Gordon Bennett (theelder).

John William Mackay (1831-1902) had made a fortune in mining after emigrating in 1840 to the United States from Ireland; in1859 he joined the rush to Nevada, where silver had been discovered. Mackay and J.G.Fair, later joined by William Shoney O’Brien and J.C.Flood, acquired control of valuable silver mines, which yielded them great fortunes.

Bennett and Mackay both used telegrams extensively in their businesses. They decided to go into the electric telegraph business in competition with the Anglo-American Company and others, which at that time had formed a syndicate known as “The Pool” that had a near monopoly of transatlantic telegram traffic, thus being able to keep telegraph rates high and profits large.

Bennett and Mackay agreed to work together to found a new transatlantic telegraph company in1883. The Commercial Cable Company quickly laid two submarine (underwater) telegraph cables from Europe, landing the North American ends at Hazel Hill, near Canso, Nova Scotia. To maintain these cables the company kept a specially-designed cable ship, the Mackay-Bennett, at Halifax, ready to go to sea at any time on short notice if a cable failed.

In the 1890s, and continuing into the 1920s, the newspapers of the day often referred to the Commercial Cable Company’s telegraph system as the “Mackay and Bennett Cable.” This was a convenient way to identify with clarity – for the general public that might not be fully conversant with the intricate details of the ownership of the various and numerous telecommunications companies – which telegraph system was meant.

Beginning in 1885, the “Mackay and Bennett Cable” was the main transatlantic competitor of the “FieldCable”, the owner and operator of the original transatlantic telegraph cables beginning in 1866.

…Oscar Lewis, of San Francisco and author of a good book (The Big Four) on the builders of the Central Pacific Railroad, has written a thoughtful history of the men who exploited Comstock’s richest ore… The men who made and kept the great Comstock fortunes were good gamblers with a certain kind of brains. Two of them, James Graham Fair, had been pick-&-shovel men in their time… A big man with a hot temper and a soft heart, Mackay became a miner for love of the exercise and a mine-owner for love of the game. InVirginia City he spent his evenings at a gymnasium taking on all comers for three bruising rounds each… By far the most generous as well as the ablest of the partners, Mackay emerges from Lewis’ account as an archetype of all that was most attractive in U.S. rich men of the era. He had many charities and gave away $5,000,000 in personal gifts before he died…

— Source:

Gamblers’ Millions Time, 27 October 1947

Cablegram vs. Telegram

A “cablegram” is the same as a “telegram” — both terms

refer to a written message sent by electric telegraph.

The term “cablegram” was used by companies such as the

Commercial Cable Company and the Direct United States

Cable Company, that had the word “cable” in their corporate

names. They were telecommunications companies exactly

like other telecommunications companies of that time

with “telegraph” in their names, such as the Anglo-American

Telegraph Company and the Western Union Telegraph Company.

Commercial Cable and Direct United States Cable preferred

not to use the term “telegram” in their advertising, because

that tended to remind their potential customers that certain

other companies, such as Western Union Telegraph or

Anglo-American Telegraph, offered exactly the same service

(delivering a written message quickly by electric telegraph

to faraway places).

The word “cablegram” rarely (never) appeared in advertising by

any company with “telegraph” in its name.

The word “telegram” rarely (never) appeared in advertising by

any company with “cable” in its name.

From the customer’s point of view, there was no difference

between a cablegram and a telegram. Many people used the

terms interchangeably – a reasonable practice because in fact

they conveyed the same meaning. For example, in movies

made in the 1930s we sometimes hear characters say

something like: “Send a cable immediately,” or “I got a cable

this morning”, using “cable” as a short form of “cablegram,”

meaning a telegram. This was a generally-understood usage

of the time.

“Upon their arrival overseas (during World War Two), soldiers

were permitted to send cable messages back home to advise

of their safe arrival – the messages were censored to make

certain that no place name was revealed.”

— The Advertiser, Kentville, Nova Scotia

24 September 2002

Here, “cable messages” simply means “telegrams”.

“Her brother sent a cable.” This line of dialog was spoken by

Oscar Muldoon (Edmund O’Brien) in The Barefoot Contessa,

a 1954 movie written and directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz,

with stars Humphrey Bogart (as Harry Dawes), Ava Gardner

(as Maria Vargas), and Edmond O’Brien (as Oscar).

Here, “cable” means “telegram”.

The online

Free Dictionary defines “cablegram” (noun)

as “A telegram sent by submarine cable.”

This definition is too restrictive. In ordinary conversation,

people using “cablegram”, to mean a written message

sent by electric telegraph, could not know what method of

transmission was used — the message could have been

sent across the ocean by submarine cable or by radio

(wireless telegraph), with neither the sender nor the

recipient knowing or caring which method was used.

To restrict the use of the term “cablegram” to “a telegram

sent by submarine cable” (thus excluding a wireless

message) is an impossible requirement. There is also

the case where a “cablegram” (telegraph message)

might be sent to its destination without crossing water

(example: New York to San Francisco) — this dictionary

expects people to refrain from using this term in such a

situation, an expectation that ignores the practical

reality that most people, probably including the editors

of this dictionary, don’t know that much detail about

the internal workings of telecommunications systems.

Another online dictionary,

WordNet defines “cable” or

“cablegram” as “an overseas telegram (a telegram sent

abroad)”. In this definition, where does a telegram sent

from NewYork to Brazilfit? Is this “overseas”?

“Overseas” or “abroad” are often used as a synonyms

for “foreign”. From New York, Brazil is definitely foreign,

but is it “overseas” or “abroad”? Is such a fine distinction

likely to be implemented in ordinary conversation?

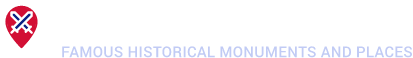

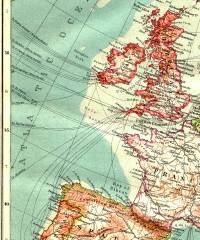

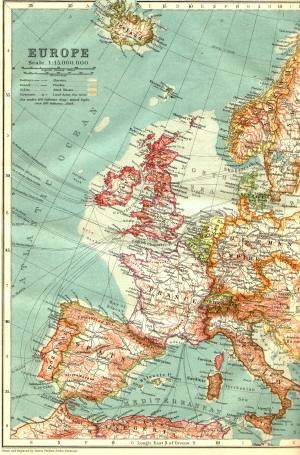

1911 Map of Underwater Telegraph Cables connecting Europe

Medium-size view 850kilobytes

Full-size view 1790kilobytes

1897 Map of Underwater Telegraph Cables in the Vicinity of Nova Scotia

Map of submarine telegraph cables in the northwest Atlantic Ocean

by the International Telegraph Bureau, Bern, 1897

History of the Atlantic Cable… (an excellent history)

New owner for old telegraph station CBC News Feb 15 2006

A community group in Guysborough County is another step closer

to saving a century-old former communication centre from destruction.

The Commercial Cable building at Hazel Hill, outside Canso, was

built in 1888 as a relay station for telegraph messages between

Europe and North America…

The station was shut down after the last message was sent in 1962.

Since then, the brick building has become a leaking, crumbling hulk.

The Commercial Cable Building Rehabilitation Society set out to

preserve the building. The local group bought the structure

using $21,000 in government funding and took possession

of it on Tuesday (14 February 2006)…

http://web.archive.orghttp://www.cbc.ca/ns/story/ns-cable-canso20060215.html

Group sends SOS for telegraph station CBC News Jun 21 2005

A heritage group fears an old communication centre near Canso

will have to be torn down if it isn’t fixed soon.

The Commercial Cable Station in Hazel Hill was built in 1888.

In its day, it relayed telegraph messages between North America

and Europe… The plug was pulled on the station in 1962.

Since then, the structure has crumbled to the point where it’s

in danger of collapsing. Now a local heritage group, the

Commercial Cable Building Rehabilitation Society, is trying

to raise the money to save the building. “Architecturally

it’s significant. It’s certainly the dominant building for this

whole eastern Guysborough County…”

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/group-sends-sos-for-telegraph-station-1.557841

Commercial Cable Rehabilitation Society

incorporated 22 March 2005 in Nova Scotia

http://www.ccrsociety.ca/

It’s now or never for Commercial Cable building

Guysborough Journal, 9 June 2005

…The decaying brick building sits on a slope over-looking Hazel Hill

Lake on highway 16. Formerly a brilliant shade of yellow, its paint has

weathered and disappeared over the years. Pigeons have invaded

its eaves and bricks have crumbled away to dust. A large building

with three to four levels, it would dangerous should it fall to the ground

on its own. The interior of the building was gutted years ago…

It now lies vacant – a curious landmark to any visitor and a part of the

landscape familiar to local residents. The brick structure that remains

today was built in 1888 to replace a wooden building built in 1886…

http://www.guysboroughjournal.com/archives/06-2005/

06-09-2005-cablebuilding.htm

Commercial Cable Rehabilitation Society meets with MLA, MP

Guysborough Journal, 18 August 2005

The Commercial Cable Rehabilitation Society met with MP Roger Cuzner

and MLA Ronnie Chisholm Sunday (14 August 2005) about the future of

the Canso Station. The society has produced a short DVD presentation

for distribution on the history of the building and the plans for

rehabilitation and presented it to the government officials.

“It went well,” says Stephen Townsend, president of the society.

“They got really excited when they saw it. Mr. Cuzner was unaware of

the history and he was quite impressed with the scope of the project”…

http://www.guysboroughjournal.com/archives/08-2005/

08-18-2005-commercialcable.htm

Hazel Hill Staff, 1926

http://www.cial.org.uk/white/hhstaff.htm

History of the Commercial Cable Company

http://www.cial.org.uk/

Note: CIAL was the Commercial Cable Company’s own telegraph code

The Commercial Cable Company, more about the founders

http://www.cial.org.uk/cable12.htm

Commercial Cable Company

http://www.atlantic-cable.com/CableCos/CCC/

Commercial Cable Company

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commercial_Cable_Company

History of the Commercial Cable Company

http://alts.net/ns1625/telegraph02.html#commcabstart

James Gordon Bennett Jr.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Gordon_Bennett_Jr.

James Gordon Bennett Jr.

http://www.grandprix.com/gpe/cref-benjam.html

John William MacKay

http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/M/MA/MACKAY_JOHN_WILLIAM.htm

The White Family Archive

George White, the last General Manager of Commercial Cable Company

in the UK, had his 100th birthday in November 2004.

http://www.cial.org.uk/white/index.htm

Maps showing Transatlantic Telegraph Cable Routes

These are excellent maps but the online version does not work

in many browsers, such as Firefox, Safari and Opera.

They do work in IE5. Netscape maybe.

http://www.cial.org.uk/wsm/maps.htm

Pacific Postal Telegraph Cable Company

The history of the Pacific Postal Telegraph Cable Company is simple.

When Mr. John W. Mackay, the famous Bonanza millionaire,

and Mr. James Gordon Bennett, of the New York Herald, associated

themselves together for the purpose of building the “Commercial” cable

across the Atlantic, they readily recognized the fact that the

“Field” cable was operated in conjunction with the Western Union lines,

and that a rival cable must be fed by friendly inland lines…

— San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser

19 February 1887

http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist11/pacificpostal.html

Nova Scotia’s Telegraphs, Landlines And Cables by D.G. Whidden, 1938

https://ns1763.ca/tele/whidden2.html

Telegraph Technology

Telegraphy by Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telegraphy

Underwater Telegraph Cables photographs of actual cables

website by Tom Perera

http://w1tp.com/mcable97.htm

1998 Diving Expedition to Recover Early Underwater Telegraph Cables

website by Tom Perera

http://w1tp.com/mcable98.htm

Telegraphic Codes and Message Practice, 1870-1945

website by John McVey

http://www.jmcvey.net/cable/ex/index.htm

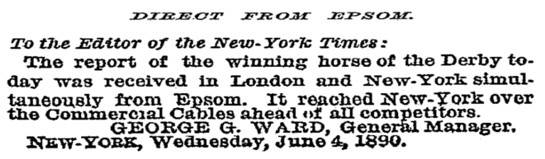

Fifteen Seconds London to New York 1890

New York Times, 5 June 1890

Perhaps some of our readers may remember having read in the newspapers of the result of last year’s (4June1890) Derby (horse race) having been sent from Epsom (Epsom Downs Racecourse near London, England) to NewYork in fifteen seconds, and may be interested to know how it was done. Atelegraph wire was laid from near the winning-post on the racecourse to the cable company’s office in London, and a telegraph operator was at the instrument (telegraph key) ready to signal the two or three letters previously arranged upon for each horse immediately the winner had passed the post. When the race began, the cable company (Commercial Cable) suspended work on all the telegraph lines from London to New York and kept operators at the Irish and Nova Scotian Stations ready to transmit the letters representing the winning horse immediately, and without having the message written out in the usual way. When the race was finished, the operator at Epsom at once sent the letters representing the winner, and before he had finished the third letter, the operator in London had started the first one to Ireland. The clerk in Ireland immediately on hearing the first signal from London passed it on to (Hazel Hill) Nova Scotia, from whence it was again passed on to NewYork. The result being that the name of the winner was actually known in NewYork before the horses had pulled up after passing the judge. It seems almost incredible that such information could be transmitted such a great distance in fifteen seconds, but when we get behind the scenes and see exactly how it is accomplished, and see how the labour and time of signalling can be economised, we can easily realise thefact…

Source:— Project Gutenberg

Scientific American Supplement, No.795, March28,1891

“…incredible that information could be transmitted

such a great distance in fifteen seconds…”

Comment: This was 1890. Only forty years earlier, in 1850,

getting information of any kind from London to New York

in ten days was considered to be very fast time. To people

who grew up in the 1840s and 1850s, fifteen hours would

seem unbelievably fast, let alone fifteen seconds. This

remarkable demonstration was an important event in the

history of communication, and it deserves to be remembered.

The Hazel Hill telegraph station in Nova Scotia was a key

(pun intended) link in this spectacular display of the

enormous revolution in the speed of long-distance

communication that had taken place within one lifetime.

Note: Electric telegraph technology of the 1890s was not able to carry a message all the way from London to New York along one continuous circuit. The distance was too great. The best they could do was to get a message through the cable under the Atlantic Ocean from Ireland to Nova Scotia, and even this was a challenge. The normal way to transmit a telegram – anything from a couple of words to several hundred words (longer messages such as government documents and newspaper reports of major events would be split into several parts with each part transmitted as a separate telegram) – from London to New York was to key it in Morse code at London while a listening clerk at the eastern end of the transatlantic cable (in this case at Waterville, Ireland) copied it by writing it on paper. At Waterville, when the message was complete the paper copy was handed to a typist at a special machine with a keyboard similar to a typewriter keyboard (except that there were no lowercase letters because all telegrams used uppercase only). This machine recorded the entire message in the form of holes punched in a paper tape. When the paper tape was completed, it was taken to a transmitting machine, which read the tape and produced the series of electrical impulses (Morse code) that went directly into the Ireland end of the transatlantic telegraph cable. The advantage, of using the paper tape to produce the Morse signals for the transatlantic cable, was that the mechanical tape reader could be adjusted much more accurately than the most skilled operator could accomplish, to produce a high-quality signal with the best possible ratio between the duration of the electrical impulses and the duration of the intervals between them. This made the best possible use of the cable by transmitting Morse code as fast as the cable could handle it but not so fast that characters were lost or garbled in transmission. At any given time, several typists were kept busy preparing tapes to keep the cable working at its maximum capacity. At HazelHill in Nova Scotia (the North American end of the transatlantic cable used for this special event) a listening clerk copied it again on paper. When this copy was complete, it was handed to another operator who keyed it into the Commercial Cable Company’s undersea cable between Hazel Hill and New York. This need, to keep the transmission distance for each stage within the limits of the available technology, introduced a series of delays that were cumulative because at each stage the telegram message had to be completed before the next stage could begin. Inthis special 1890 demonstration (described above) these cumulative delays were reduced to a minimum by four strategies: (1)bystopping all other message traffic along the system, they eliminated the need for the telegram to include a destination name and address (two or three dozen characters) because there would be only one message in the whole system and everyone in the Commercial Cable Company knew in advance exactly where that one message was togo, (2)byreducing the length of the message to only three characters, (3)byeliminating the written copies at London, Waterville and Hazel Hill – including the Waterville punched tape which for this very special event was bypassed by connecting a high-voltage telegraph key directly to the transatlantic cable, and (4)bystarting the retransmission at each stage before the incoming message was completed. Ofcourse, (3)and (4)were made possible by(1)and(2).

— ICS, 26 June 2009

Morse Code Keying Standard

Dashes are to be three times as long as dots.

Spacing between parts within a character to be equal in length to a dot.

Spacing between characters to be equal in length to a dash.

Spacing between words to be equal to seven dots.

Source: CQ Radio Amateurs’ Journal January 1954, page 31

http://hamcall.net/cqcgi/?res=l&yr=1954&mo=01&pg=001

Hazel Hill Historical Mistakes

As everyone knows, some of the information found on the Internet is wrong.

Here’s a prime example, describing the Commercial Cable telegraph office at Hazel Hill:

“This is the place where the first transatlantic cable

from North America to Europe connected and where the

first distress message from the Titanic was received.”

— Source

http://www.whitmania.com/pdpdpd/album/places/Cablehouse.htm

There are two major mistakes in this single sentence.

(1) “This is the place where the first transatlantic cable

from North America to Europe connected…”

This is flat wrong, by 25 years and hundreds of kilometres.

• The first transatlantic cable that came through Hazel Hill was the cable laid

in 1883 by the Commercial Cable Company.

• The first transatlantic cable from North America to Europe was laid in1858,

and it “connected” (came ashore) at the head of Trinity Bay, Newfoundland.

(2) “…where the first distress message from the Titanic was received.”

• The first distress message from the Titanic was not received at Hazel Hill.

• No messages from the Titanic, distress or otherwise, were ever

received at Hazel Hill.

• All of the messages from (and to) the Titanic on its voyage across the

North Atlantic in 1912 were transmitted by Marconi wireless (radio).

• The Commercial Cable Company telegraph was not a wireless system.

It was a wired system. All messages through Hazel Hill were carried

by wire – overland by iron wire and underwater by copper wire.

The Commercial Cable Company telegraph most emphatically was not a

wireless system. Marconi’s then-new wireless was a deadly enemy of

all wired telegraph companies, such as the Commercial Cable Company

(at Hazel Hill, Nova Scotia), and the Western Union Telegraph Company

(at Canso, Nova Scotia), and the Direct United States Cable Company

(at Halifax, Nova Scotia), and all the others.

• The main flow of Titanic message traffic was handled by Robert Hunston

and Walter Gray at the Marconi shore station in Cape Race,

Newfoundland. All messages from the Titanic were wireless (radio)

messages. The distress messages sent from Titanic during the

night of 14-15 April 1912, were received by several ships, and on

shore by the Cape Race wireless station which then sent them toward

New York by the Western Union telegraph (using an overland wire

supported at the top of hundreds of wooden poles). None of this

traffic went through the Commercial Cable Company telegraph station

at Hazel Hill. The Western Union Telegraph Company was a

competitor of the Commercial Cable Company, and carried its traffic

on its own lines rather than allowing the competition to share

in the revenue.

No messages from the Titanic were received at the

Commercial Cable Company in Hazel Hill, Nova Scotia.

The Commercial Cable Company had no wireless equipment.

Many amateur historians fail to heed the important distinction between

wireless telegraph (radio) and plain telegraph (carried by wires).

It is a major difference, but many historians confuse them, mixing

one with the other and thus mangling the historical record.