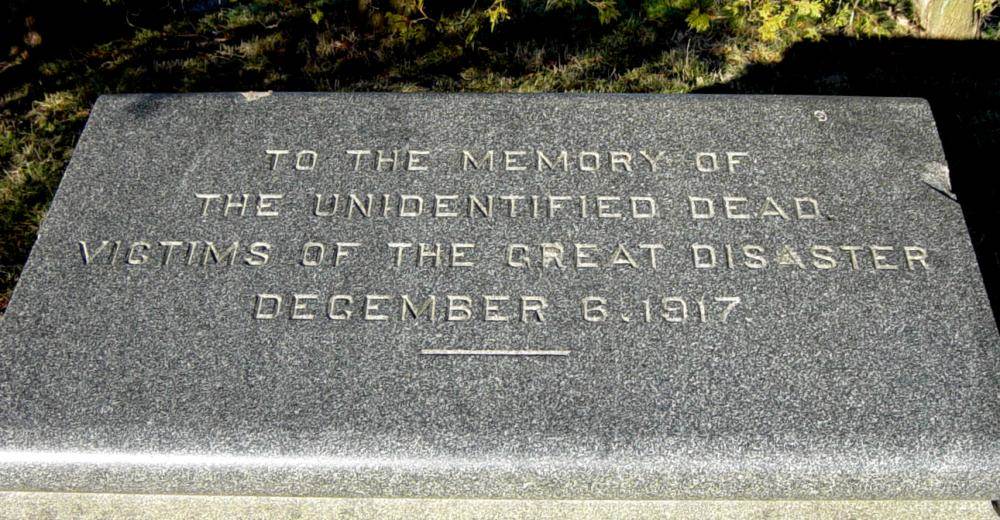

Unidentified Dead Halifax Explosion

6 December 1917

Photographs of Memorial

Halifax, Nova Scotia

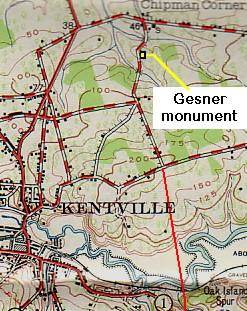

Located on the north side of Bayers Road,

about 40m east from the railway overpass.

GPS location: 44°39’13″N 63°37’25″W

Photographed on 4 January 2006

Photographed on 4 January 2006

Photographed on 4 January 2006

Photographed on 4 January 2006

Photographed on 13 January 2006

Looking northwest across Bayers Road

Photographed on 13 January 2006

Also see: Vincent Coleman’s tombstone

Halifax Explosion by Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halifax_explosion

Photograph, Public funeral of unidentified dead

Halifax, 17 December 1917

http://www.gov.ns.ca/nsarm/virtual/explosion/archives.asp?id=34

Photograph, Protestant service at funeral of unidentified dead

Halifax, 17 December 1917

http://www.gov.ns.ca/nsarm/virtual/explosion/archives.asp?id=43

Photograph, Roman Catholic service at funeral of unidentified dead

Halifax, 17 December 1917

http://www.gov.ns.ca/nsarm/virtual/explosion/archives.asp?id=42

Canadian Disasters, An Historical Survey

http://web.ncf.ca/jonesb/DisasterPaper/disasterpaper.html

Explosion vessel’s remnants lie in Falklands

Two days and five flights took Hubert Hall from Yarmouth County nearly to the shores of Antarctica.

On a small piece of land in the Falkland Islands, he got in a Land Rover and drove another three hours over rocky coast and peatbogs.

And there —11,000kilometres from Halifax— was something with great historical significance for the city, though few human eyes have seenit.

A ship once called the Imo, a smallish ocean liner later converted into a whale oil carrier, has lain there wrecked for 90years.

Once upon a time, its pilot stubbornly refused to give way for another ship in the Narrows of Halifax Harbour, and the other ship’s pilot also navigated sloppily. The Imo ground into the side of the Mont Blanc, where the sparks started afire.

About 20 minutes later, on Dec. 6, 1917, the explosion of the other ship’s volatile cargo laid waste to two square kilometres of the city, killed almost2,000 and injured9,000.

Though memorials to the Halifax Explosion dot the city and its lessons are taught in schools, few Nova Scotians know that one ship survived, was patched up and went on to a new career in the SouthPacific.

And only a very few dogged travellers have visited the last remnants of that ship, where it was finally grounded off the Falkland Islands in 1921. In mid-November, Hall, a retired Marine Atlantic captain, became one of them while in the Falklands for a tour with hiswife.

Getting to the wreck meant passing a colony of majestic king penguins, but they were just a side attraction, said Hall. “It was pretty exciting,” hesaid.

“The tide was down low enough that we could see what they think is the boiler sticking up out of the water, about 200 metres offshore. And looking around on the rocks there was this big anchor and piles of anchor chain and some other small bits andpieces.

“It’s such an important part of Halifax and Nova Scotia’s history, and here Iam looking at it and sitting on it,really.”

The Imo’s end off the Falklands is well documented, said Richard MacMichael of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic inHalifax.

“Everyone knows what happened to Mont Blanc because people were finding pieces of the ship,” hesaid.

“But for Imo, her story goes on and not a lot of people know it. And that’s unfortunate because, in all four of her lives, she had a really interesting career.”

The Imo was blown ashore in Dartmouth by the explosion, with its captain and bridge crew killed. But by the following July, it was back in the water and heading to New York for repairs. The name was changed to the Guvernören, and it was sent south, never to return toHalifax.

The Imo saw a lot in its 32 years. Built in 1889 by White Star, the same company that built the Titanic, it was first called the SSRunic, then the Tampican, and transported passengers on the Atlantic. In1912, it was sold to Norway’s South Pacific WhalingCompany.

The owner of the company, Johan Martin Osmundsen, tried to name the ship with his own initials —JMO— but when people started calling it Imo, the name stuck, saidMacMichael.

After the explosion, it was sold to another Norwegian company.

Superstition around the huge loss of life in Halifax wouldn’t stop anyone from taking on the Imo in a “waste not, want not” era, MacMichael said. After all, even the lifeboats from the Titanic were quietly put back into circulation after a new paintjob.

“For anyone that was looking to add a ship to their fleet, here’s a vessel that’s had a little bit of damage —pick it up, dust it off and send it back out in the water again,” hesaid…

Halifax Explosion vessel’s remnants lie in Falklands

— Halifax Chronicle-Herald, 6December2011